All corners of the agriculture industry—from farmers to environmentalists to scientists—are honing in on what the United Nations calls "our silent ally in food production."

That is how José Graziano da Silva, director-general of the Food and Agriculture Association (FAO) of the United Nations, characterized soils in anointing Dec. 5 as World Soil Day in 2014. Now an annual event, it has positioned soils front and center as a major resource in the quest for global sustainability. The effort received an added boost when 2015 was designated the International Year of Soils.

Ninety-five percent of the world's food comes from the soil. When viewed in the light of a projected 9 billion mouths to feed by 2050—and the need to produce 70 to 100 percent more food than we do today to meet that demand—preserving soils is unarguably crucial. "Feed the soil, and you feed the world," said Robert Walker, general manager of Alltech Crop Science, a division of Alltech, a leading global biotechnology company headquartered in Nicholasville, Kentucky.

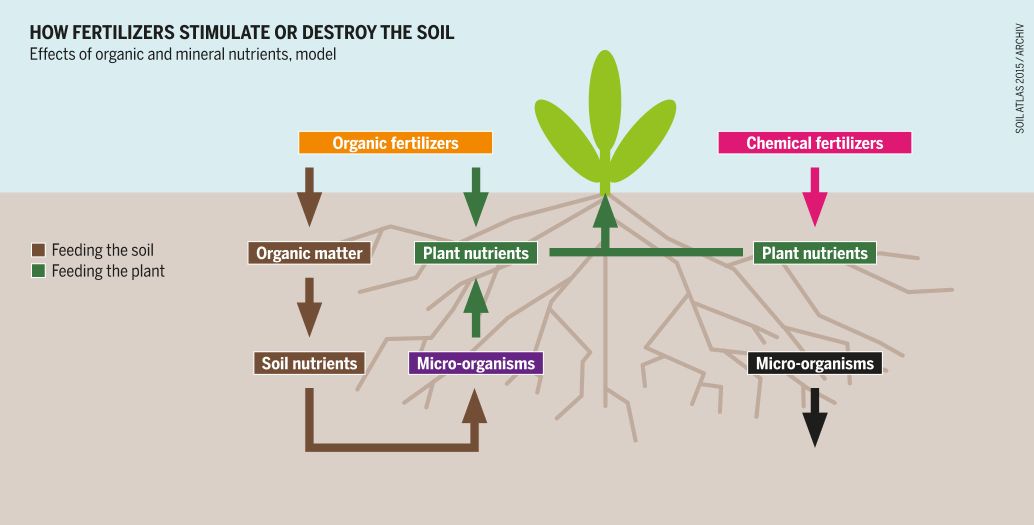

The key to achieving that goal rests in how we handle our stewardship of the soil, he said. Modern agricultural practices using chemical fertilizers and other non-organic methods of feeding the soil have "worked" in terms of the end result. However, in the process, these synthetic compounds have destroyed beneficial microbial communities that can aid in neutralizing toxic compounds in the soil and improve soil health.

Saving the soil doesn't mean mounting a standoff between conventional and a more natural farming approach. The most effective way to feed the world, said Walker, is to develop natural farming principles and combine them with modern science. New microbial technologies, he said, are enabling us to return organic matter to the soil. "There is an opportunity in organic fertilizers, new biological technologies and precision agriculture," he said.

The take-home message, said Dr. Steve Borst of Alltech Crop Science at the 2015 Alltech REBELation symposium, is clear. To move toward global sustainability, he said, "We need to work with nature, not against it." In practical terms, that translates to: Don't just grow crops; grow soil.

Soil analysis at the Alltech research lab in Dunboyne, Ireland.

Microbial research offers a bridge to more natural methods of producing healthy soil than have traditionally been used. Since the 1930s, when synthetic pesticides were invented, the standard approach was to use chemicals to eradicate rather than grow microbes in the soil. That sprung from a misconception that all microbes, because they are bacteria, are harmful to crops. But just as researchers learned that beneficial bacteria can be used to aid digestion in both humans and animals, the same is true for microbes in plants. Consider them a sort of "probiotics for crops."

Alltech's methodology—deploying microbes in the soil as weapons with the ultimate goal of improving plant health—is the most direct way to take advantage of microbes in farming, said Borst. It also benefits the environment because it reduces the need for pesticides. "Synthetic chemistries are not the only way to combat the challenges we face in agronomy," he said. "Integrating microbial control measures and natural technologies into our protection programs can give far better long-term results."

Walker sees microbes as a treasure trove for the planet. "Beneath our feet we have this world of microbes that can benefit human health, animals and the environment," he said, noting that researchers have only discovered 1 percent of the life in the soil. "Imagine what we could find if we tapped into the remaining 99 percent."

That is precisely what Alltech's researchers are sleuthing through the use of DNA sequencing and other cutting-edge technologies that have opened up the heretofore-secret world of microbes.

"We are researching genetically what these microbes are. Not many research groups are doing that," said Walker.

While impressive, he considers that just the threshold. "It is not enough to identify new species of bacteria in the soil and how they could be beneficial," he said. Just like the soil itself and the crops grown from it, the microbes have to be sustainable. "We need to design techniques and preparations so that the microbes we are spreading survive the journey."

Alltech is developing techniques that "allow us to encapsulate these microbes so we can actually harness their nutritional value, and we need to learn how to make them viable longer."

That has been difficult to achieve using common agricultural techniques that rely almost completely on pesticides. Farming implements, said Walker, are often highly pressurized and contain harsh chemicals, which can kill the living microbes before they are even applied to the plant.

"In addition, if we are looking to encourage the growth of microbes in our soils, we need to adapt our management techniques to make sure that we are not unintentionally countering the growth of microbes by using incorrect management practices," he said.

Creative Commons - "How fertilizers stimulate or destroy the soil" by Soil Atlas is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Alltech has developed an extensive multi-tiered approach over the past two decades, recently stepping up its efforts by opening additional research centers. In the past two years, the company built research facilities in Ireland and Brazil and is looking into the possibility of another. In addition, Alltech has established research alliances with numerous universities across the globe.

There can also be a financial upside, which is always welcome news for farmers. "Microbes in soil make the plant more resistant to pathogens," said Walker. "By adding microbes to the soil, it can add a lot of money to your yield. It's a business that is going to double in value."